By Regina Villiers. Originally published January 20, 1993 in The Suburban Life, added January 14, 2017.

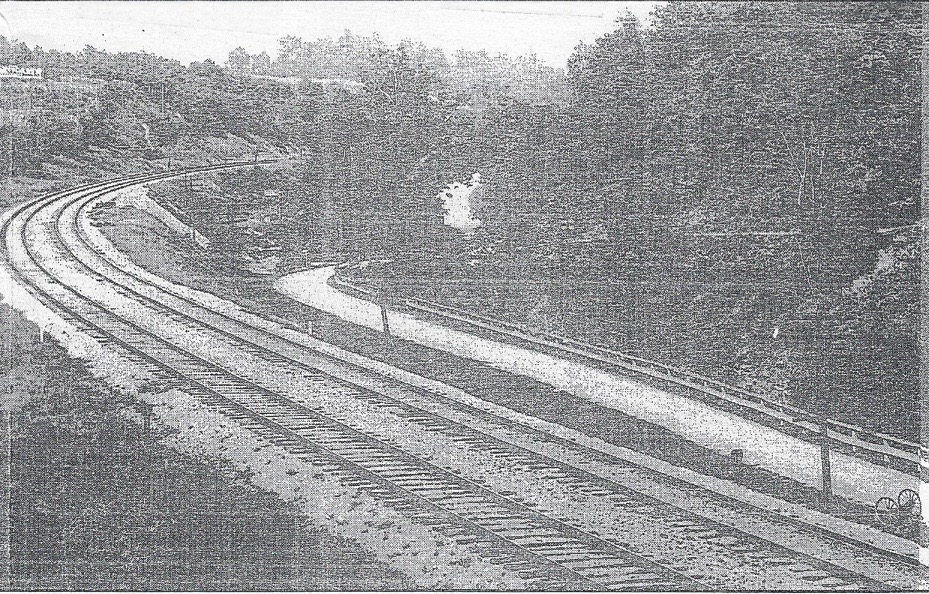

The B & O train tracks going east, out of Madeira, beckoned Brownie Morgan and his friends when they were boys, luring them with promises of adventures and treasures. Riches like coal for the family stoves and fresh wild strawberries for shortcakes were theirs merely by following the tracks.

While I always happily accept any suggestions for columns and explore all possibilities for stories, many of my Madeira stories comes from two sources – Miss Cleo V. Hosbrook and Brownie Morgan.

Miss Hosbrook’s ancestors were the backbone of Madeira. They were here at the beginning, and she has spent her entire life collecting their stories and pictures.

I have known her for a long time, and she has generously passed on to me those stories and many of the pictures. To a writer, there is no greater gift.

And having Brownie and Helen Morgan for friends and penpals is like owning my own gold mine. When a letter comes from them, it brings a warm glow, as if the mailman had just brought me a bag of nuggets.

Brownie, listed on his birth certificate, as Durward, is not listed on his resume as a writer or historian. He would deny being either, but he is both.

Brownie has lived most of his life in Madeira, and he has almost total recall of his life there. For several years, he has been writing down for me, in letter form, his memories of what it was like to grow up in Madeira.

His letters form a thoughtful and vivid history of Madeira, full of details and glowing memories. I always await the next letter.

A recent letter from Brownie, a 19 pager, contained his memories about trains and the part they played in his life as he grew up and first went to work.

In the early part of this century, trains were the lifeline of Madeira and the link to the world for its people.

To boys Brownie’s age, trains brought dreams of far away places and gave them many everyday activities.

As a child, Brownie remembers taking a shortcut by the train station every afternoon on his way from school to his home on Laurel Avenue.

Every day as he passed, he would see Mr. Ogier, the station master, busy with paper works as he sat in a swivel chair behind a wide shelf that fit the contour of the bay window on the side of the station.

On the shelf sat a ticking Morse code device and a black, upright telephone with an earpiece hanging on the side of it. There would always be a pile of papers in front of Mr. Ogier. Against the wall, behind Mr. Ogier, stood a roll-top desk with lots of pigeonholes stuffed with pink, white and yellow papers.

Brownie says that when he was a boy, there was little territory that he and his friends did not explore. That included the railroad and the destinations of the tracks.

Most of their explorations were spontaneous and unplanned except for their wild strawberry excursions.

Outside of Remington, a steep bank by the railroad tracks was covered with wild strawberries, small but tasty.

At ripening time, the boys would take their small buckets and walk east on the tracks to search for shortcake material and to get themselves some good behavior points with their parents.

Their parents taught them to walk the same track as the oncoming train, so as not to suffer the same fate as two young men they knew who walked with artificial legs – though it was said their legs were the result of hopping freights, and Brownie’s group never hopped freights.

Walking the tracks was useful in another way to Brownie. Coal would fall along the tracks from coal cars, sometimes big lumps of it. People made a habit of collecting it for their cook stoves or pot-belled stoves in the parlor.

During the Depression, Brownie helped his own family by collecting coal along the tracks. By calculations, he learned to estimate a starting point so that he could fill a feedsack with coal on his way home, just to get it filled by the time he reach his house.

The railroad also provided summer vacation jobs for the boys. The job was to keep the roadbed free of weeds and trash by attacking the weeds. Long about July and August , these jobs were ordeals. John Laffey Sr. was a section crew foreman and the boss of the track-cleaning boys.

The train crews were always friendly would wave to everyone as they passed through Madeira. Brownie remembers the engineers. They always sat relaxed, with their elbows sticking out the windows, their forearms resting on the cab window sills. The man at the end of the train would always have the same posture as he sat high in the caboose.

Brownie was fascinated with the handcar. He saw it as a great potential for fun and personal freedom, though he never got to try out his fantasy.

His favorite train car was the dinning car. He could view such grand splendor at such a close range. People were all dressed up, even on work days, children too, sitting with their parents.

The tables were draped with fine linen tablecloths with matching napkins bigger than Brownie had ever seen and white as new snow.

The silverware, he thought, must have been made of pure silver, for it was polished to the highest degree. A crystal vase holding single, fresh rose sat on each table, placed there with a high regard for conformity.

The engines put out a lot of black smoke and cinders, and all windows had to be closed before entering a tunnel, which made the coaches very hot.

Brownie discovered just how hot those coaches got when he took a train ride at age 17 in 1926. With his sister, Elsie, two years older, he went back to the place of their birth.

Brownie’s adventures with trains did not end with his boyhood years. They continued after he grew up and went to work at his first grown-up job.

But that’s another story.