By Regina Villiers. Originally published August 6, 1997 in The Suburban Life, added August 12, 2018.

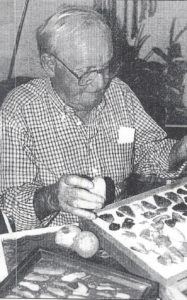

Dallas Burton pores over some of his “rocks” and archaeological artifacts.

Dallas Burton remembers the first arrowhead he ever found. It was a Hopewell dovetail, and he was about 6. That launched him into a lifelong hobby and propelled him on his way to becoming an amateur archaeologist.

Dallas grew up on a farm in Cozzaddale after the Depression. Farm kids lived close to nature and made their own fun and leisure time pursuits. They did not squander money on recreation.

At a recent meeting of the Madeira Historical Society, Dallas talked about his idyllic childhood and his adventures in archaeology.

“Hunting arrowheads was the freest thing in the world to do,” he said. “If you didn’t hunt on your own land, all you had to do was to get permission.”

His early treasures were all surface finds, but good spots to look, he said, were around stumps from trees that had been cut down. Many also could be found while doing farm work and plowing in the fields.

When World War II came along, Dallas went into the Navy. His artifact hobby was put on the back burner and out of mind.

But unlike mothers who dumped their kids’ shoeboxes of baseball cards when they went away, Dallas’s mother preserved his Indian artifacts and his “rocks.” She saved them, and after he came home from the Navy, she reminded him and told him they were in the basement.

This gave him the enthusiasm to jump-start his hobby and to start out looking again.

Now, he sometimes wishes he had gone to college after the Navy and studied archaeology. But he didn’t. There was a living to be earned, and other things called. But, although he doesn’t have the college degree, Dallas had much of the knowledge.

He has spent a lifetime of reading and studying. When he makes a find, he knows what he has found. He goes to meetings and exhibitions. He belongs to groups, such as the Central States Archaeological Society. He reads and studies their journals.

After he married, his wife, Doris, also was interested in the subject. Then, their three daughters grew up interested in it. Dallas discovered that his hobby was a good family pursuit, something they could do together.

“It was something I could do without deserting my family,” he said. “I included them and took them along with me a lot of the time.”

He also made friends with those interested in the subject who shared his enthusiasm for his pursuit.

“I’ve met so many nice people, because of it,” he said. Some of those friends live in Kentucky, where he has gone on hunting expeditions.

“I always get permission,” he emphasizes. “That’s important to me. I would never look or take anything without permission.”

Dallas has studied Native American history and culture. He not only knows about the items he finds, but also knows who made them and why.

“Survival was what it was all about,” he said. “They made and used these things to survive.”

He said that Indians settled where water was available, for use for transportation, and where they had hunting and also clay and stones for tool making. He cites Mariemont as and example where all these needs were available.

“Everything they made had a purpose,” he said.

He points to knives and scrapers, used for skinning and chopping. There were flake knives, made of quartz, and thumb scrapers. They made all their tools, he said, including hammer stones, used to chip out bladelets and knives.

Dallas can tell at a glance what the various stones are-quartz, flint- and where they came from, such as Flint Ridge cores, and what tribe used them. He has read and studied, making himself into an expert on Indian archaeology.

Recently, Dallas got away from artifacts and went back to memories of World War II. During the war, he served in the Navy on the aircraft carrier, the San Jacinto, along with former U.S. President George Bush.

Dallas attended a recent ceremony about a painting of the San Jacinto, by Ohio artist Tom Stahl. The painting will be hung in the Bush library, which will open in November at Texas A&M University. Along side the painting will hang a brass plaque with 153 engraved names of the crew of the San Jacinto, who contributed money and memories to the project.

Dallas Burton’s name is on that plaque. He’s proud of that.

He’s also proud of his archaeology efforts and the pleasure it has given him.

“I still get enjoyment from it,” he said. “You never find two that are the same. And I’ve met so many nice people.”

And we can all be thankful that his mom didn’t dump his collection when he grew up and went away to the Navy.