By Regina Villiers. Originally published April 15, 1992 in The Suburban Life, added July 12, 2014

From the first time I saw her, I wanted to know her. I could tell she was unique and that she had to been an interesting person. She set herself apart, giving herself an air of mystery. The sight of her made me think of Greta Garbo and her famous line: “I want to be alone.”

Of course, immediately after moving to Madeira, I learned about the Hosbrooks. The Hosbrooks had owned, in the early days, most of Madeira, it was said.

And much of the part they hadn’t owned had been owned by the Muchmores, the other side of Miss Cleo’s family, back in the days when Madeira was farmland.

From the beginning, I bumped into her constantly. I’m a walker. She walked everywhere, it seemed. My second home has always been the library. She always seemed to beat me there.

I’d see her in the local grocery around the corner from her house. She bought a lot of cat food, giving me a kinship. I, too, bought a lot of cat food, for my beloved Claude.

I’d walk past her house, which sat next to a larger, old Victorian house. The two of them, plus an intriguing building in back, all enclosed by iron fences and gates, nestled there, like three jewels, I thought, in the very heart of downtown Madeira.

I’d see her at both houses and working in both yards. I learned that she owned the three buildings, lived in the smaller house, and that the larger one and the barn had belonged to her grandparents.

Whenever I’d see her there, or out and about, I’d give her a friendly hello.

She’d smile a small, polite smile and answer “Hello” in a most gentle voice. That’s all. I’d get no more from her.

The first time I talked to her, other than a hello, happened one evening on Miami Avenue. As I approached her in front of an old house, she was snapping pictures with a camera.

“It’s going to be torn down tomorrow,” she said. Her voice was sad. “I just wanted to get some pictures of it.”

From then on, as Madeira changed and moved toward progress, I would see her at every doomed building before the razing, recording it with her camera, as if her pictures would keep it in existence.

I finally broke through into her world one election day. I started working in my polling place as a poll worker and I discovered right away that Miss Hosbrook voted in my precinct.

There she was, coming through the line to vote. As I gave her a ballot, I blurted out, “Miss Hosbrook, I love walking past your yards, because your flowers are like my grandmother’s flowers, and your curtains are like my grandmother’s curtains, and I loved my grandmother.”

A beautiful smile lit her face. “The next time you pass,” she said, “why don’t you come inside and look at them close up? I’ll show you around.”

That invitation marked the beginning of one of the best friendships I have known, with one of the most remarkable and interesting women.

At once, I discovered her to be generous. If she likes you enough, she will give you anything she owns.

Her gifts are real gifts, of herself. She has passed on to me many of the small treasures of her life, items that mean something to her.

The gifts would always be wrapped, in old interesting wrappings. I saved them and treasure them almost as much as the gifts. One was tied with an exquisite length of very old ribbon.

She has given me old, glass paperweights, books, pictures, photographs. My house is dotted with bits and pieces of her life.

On my kitchen window sill, the morning sun sparkles from jewel-like geode rocks she gave me. All the time, I wear a large ring of hers that she passed on to me. It’s heavy, carved silver ring, bearing the masks of comedy and tragedy.

I told her I wear it with the comedy side facing me, so that I smile all day long. “But,” she said, “Then everyone facing you gets a frown.”

My yard is laced with “starts” that she has given me of most of the flowers in her yard, including the antique roses, which I started from cuttings under jars.

She has a puckish, impish sense of humor. It’s so dry and intellectual that it will slip by you if you’re not alert.

She also tells funny stories. Even now, when she has so little to laugh about, she’ll tell me funny stories that happened in her childhood and stories about her family. She makes herself the butt of most of her humor.

She likes children. Until she retired, she taught second grade at Condon School.

She learned about my youngest son early on. She liked to tease him about the amount of ketchup he put on his sandwiches and accused him of eating ketchup sandwiches.

She likes poetry. She used to copy whimsical little poems and make them into greeting cards to send to me. She loves mail and has written me stacks of letters. Her cards were all handmade.

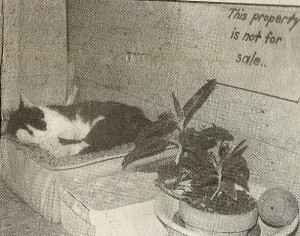

She’s a compassionate person who loves nature, plants and animals.

Any stray cat who ever found its way to her door was given a name and a great life. She fed and treasured them all. Her life has been marked by a long line of beloved pets. She still watches nature, one of her few remaining joys.

She has her birdfeeder outside her window, and she wheels herself each evening up to a window in the dining room where she can watch all the birds go to roost in a large evergreen tree.

She always strived to continue learning. Once, I met her on a frigid, blustery day as she fought her way up the street, looking as if she’d blow away.

“Where are you going, Miss Hosbrook?” I asked.

“To the library,” she said. “I need to look up ‘boondocks.’ I have an idea of what it means, but I need to know exactly.”

English she can handle. Modern slang sometimes gives her trouble.

She still tries to learn, though her world has shrunk. Recently, she asked me the name of a plant she couldn’t remember. When I told her, she wheeled herself over to her pad and pen, always available, and started writing it down. “Next time, I won’t forget it,” she said.

She still gives to me, too, whatever she can. Her most recent gift was a placemat on which her dinner was served. She did not use it, but folded it and saved it for me. It had some obscure Ohio laws printed on it. “You’ll get a laugh out of this,” she said, as she presented it to me.

After she went into the nursing home, she had a box of photographs sent to me. Some are treasured old family photographs. Some are a part of the hundreds of snapshots she continually took of all the parts of her daily life.

Even more special to me are the pictures of her in my heart, which I see when I close my eyes. I see her sitting in a lawn swing in back of the Muchmore House of her grandparents.

The Sunday newspaper is spread out around her in the swing, as she holds the Sunday cartoons. Snow covers the ground around her. I see her standing beside a 7 ½-foot tall tiger lily in her yard.

I see her pride as she pointed out to me the stepping stones around her houses which were made by her Grandfather Muchmore. I see her photographing the pumpkin display at Gary Allman’s Curious Garden. Most of all, I see the glow in her eyes as she told me about her father pulling her in a red wagon around the Christmas tree when she was a little girl.

These images will stay with me always, to remind me of the joys of having such a rare friend.

Getting to know her wasn’t easy. Actually, getting close to the highest pinnacle of Mt. Everest might have been easier. But knowing Miss Cleo Hosbrook fills me with much more pride and a great deal more pleasure.

A cat sleeps on the back porch of the Hosbrook House, where numerous inquires prompted Miss Hosbrook to post this sign.