By Regina Villiers. Originally published March 17, 1993 in The Suburban Life, added November 2022.

Keiko Hirano of Tokyo first cast her spell on Madeira in 1939 when she came to Madeira High School as an American Field Exchange student.

Madeira gets an exchange student every year. No big deal, but Keiko was a big deal. From the beginning, it was mutual bonding.

At the end of the year, Keiko liked Madeira so much that she wanted to stay and graduate with her Madeira classmates. Her AFS stay only lasted a year, but her father made arrangements for her to return on her own for her senior year at Madeira.

This was unprecedented. Principal Martin H. Strifler said no exchange student had ever returned for a second year.

I first met Keiko in the journalism class, where I was the community advisor. She amazed me with her maturity and in dependence, far more advanced than most teenagers I saw. She quickly mastered the cultural differences and attacked everything with energy.

She wrote a column regularly for the school newspaper, about being a student and a teenager in Japan. She worked diligently and would bring me rough drafts of her columns well ahead of time, begging me to tell her how to improve them.

“She was so eager to learn,” said Dawn Stewart, one of her Madeira teachers. “If I said something in. class she didn’t understand, she’d whip out her little Japanese-English dictionary and start flipping pages.”

During her senior year, Keiko decided she wanted to go to college in America. She visited colleges and made applications. including Trinity College in Washington, D.C. She flew there alone and took the subway out to the school. “I’m used to the subway,” she said. “In Japan, we have really useful subway and train systems.”

She soon discovered that it would be impossible for her to attend college here and was disappointed to learn that a foreign student was not eligible for scholarships.

After graduation, she returned to Tokyo to attend college. Temple University in Philadelphia has a branch college, Temple University Japan in Tokyo. Keiko studied and worked hard there, determined to succeed.

After her return to Japan, we became great penpals. She’d write me long letters, telling me about her life there, and asking me to correct her English. There was nothing to correct. They were wonderful letters.

She told me about her college life and her weekend job at Tokyo Disneyland. She described the Japanese summers – the rainy season, the heat and humidity. She wrote about the fireworks festivals and the many summer’s_ night community

festivals. She described the food stands, the drinks, the watermelon, the toys and the performances.

She told me how the people wear the yukata, to escape the heat. The yukata is a casual kimono, more comfortable than the kimono, cooler and easier to put on.

She told me about the furin. “Furin is like a bell,” she wrote, “to put under the roof. It makes very cool sound. If you feel very hot, you just listen to the ringing. It will cool you off a lot.”

At her university, she spoke English with her professors, and she spoke Japanese at home with her family and friends.

Keiko’s family consists of grandparents, parents, and two younger brothers.

In Madeira, her American family was Bill and Kay Caesar. The bond between them and Keiko was, and still is, quite close.

Keiko’s parents visited in Madeira the first year she was here, and her father came back to see her graduate. Last summer, the Caesars visited Keiko’s family in Tokyo.

On the last day of July 1992, Keiko finished her freshman year at Temple Japan, elated that she came through her English essay class of 20 students with the highest score.

She spent her one-month summer break before the fall semester by working fulltime at Tokyo Disneyland.

Keiko’s greatest attribute is her enthusiasm for life and everything and everyone she touches. She loved her job, her classmates, her friends, her family – her life.

But deep inside, she had a longing to come back to America. “I feel in between Japan and the U.S. very much,” she wrote me. “Can you understand what I mean?”

So in January, she transferred to Temple University in Philadelphia, where she will complete her sophomore year this summer as an accounting major. “I want to have a license,” she said, “so that I can always get a job.”

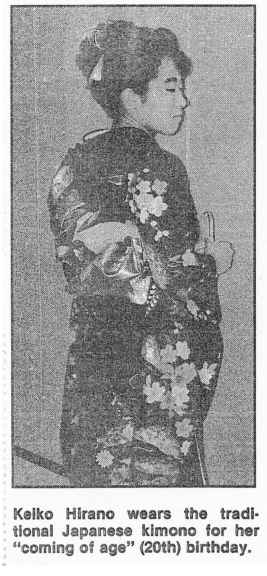

Before she left Japan, she took part in an important ceremony with her family. Last August, she reached her 20th birthday, which is the “coming of age” birthday in Japan. All 20th birthdays are celebrated in Japan on the following Jan. 15, with a day of pageantry and rituals, with everyone wearing kin1onos and traditional Japanese dress.

Because Keiko would not be in Japan on Jan. 15, she celebrated early before leaving for Temple. Her family and friends, with pomp and circumstance, helped her become an adult.

On her way to Temple, Keiko stopped off in Madeira for a week, staying with the Caesars and visiting all her Madeira friends, including Dawn Stewart, her “favorite” teacher. “She played the piano for us,” Mrs. Stewart said, “beautiful classical pieces.”

Keiko likes to say that she was named for her mother. Aptly, it means in Japanese: “Fortunate girl.”

Fortunately, for us, Rudyard Kipling was dead wrong when he wrote “East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.”

East did meet West, right here in Madeira. And we are fortunate for that meeting.

Regina Villiers is a writer who has lived in Madeira for 25 years. Her column appears reg-11larly in the Suburban Life-Press.