By Regina Villiers. Originally published July 27, 1994 in The Suburban Life, added December 18, 2018.

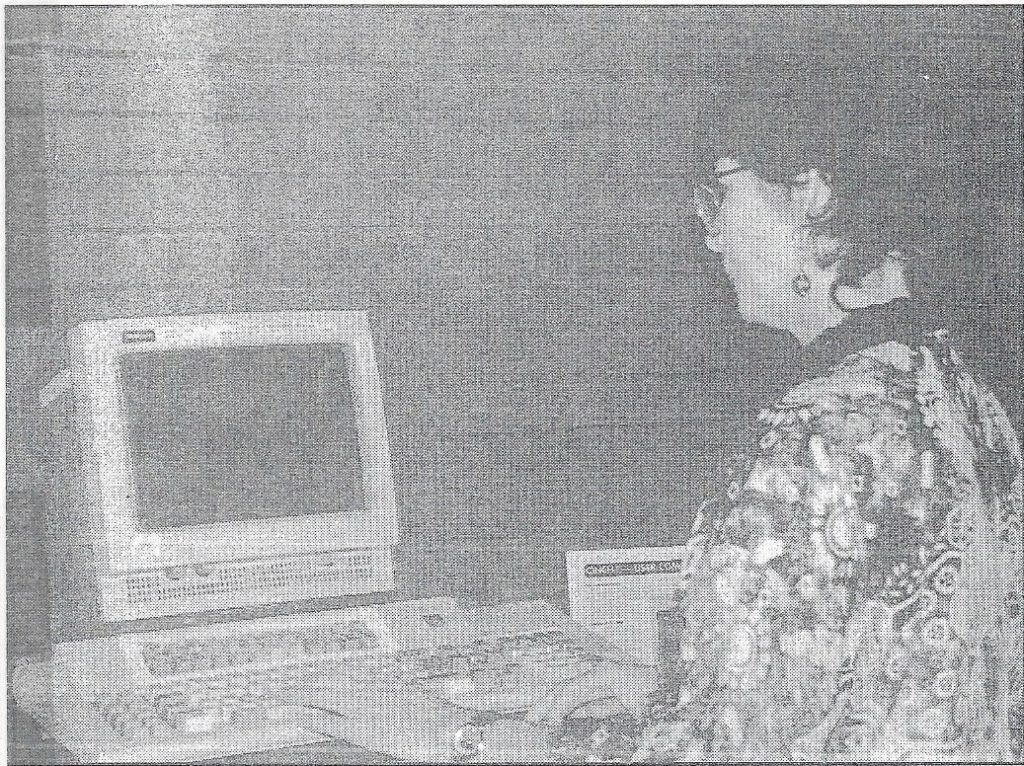

Beverly Wilson, a librarian at the Madeira-Indian Hill-Kenwood Regional Branch Library, demonstrates the computerized card catalog, which she says is easier, saves time, and offers more to the user.

You need to know that I don’t give things up easily. I want to hold on to things that I like. Though it’s probably dime store quality, I use my grandmother’s sugar bowl daily. But I prefer it to fine china because the scratches and nicks in it were put there by clinking spoons on my grandma’s table.

In my house I have two black rotary dial phones in regular use. I do not intend to dump them. And I listen to Dusty Rhodes’ oldies show on radio every Sunday night, sometimes tuning him in on my 1928 Zenith console radio.

No, I do not give up the old for the new too easily, so when the Madeira library put their cards on computers over a year ago, I greeted the change with alarm.

I could see not need for the change. I’d never had a problem with the card catalog. Actually, I’d thumbed through it so much that I knew many of its fingerprints, and I felt devotion for it. I loved browsing through it.

I did not complain outwardly, but inwardly I stewed. I avoided using the new computerized system and I often wondered what really happened to the old card catalog with all the information and the scribblings on the old, well-worn cards that had served me for so long.

I missed seeing the old cabinets sitting there when I walked in. Some of the charm of the library had dissipated.

Then in April of this year, Nicholson Baker wrote an article, “Discards,” in the New Yorker about the scrapping of card catalogs in libraries across the country in favor of computer systems.

A comprehensive, well-researched piece of writing, it explored both sides of the issue. It gave the libraries reasons for dumping the card catalogs, but it also gave good reasons for why they should have been kept. This seemed to be the view of the author.

The article struck a nerve with me and nagged at me until I read it again and again. My mourning for my own card catalog resurfaced and would not go away.

Finally, with notebook in hand, I went down to the Madeira library to seek answers and talked to Beverly Wilson, one of the five librarians there.

Ms. Wilson, originally from North Carolina where she worked in school libraries, has been a librarian in Hamilton County for six years. Before coming to Madeira, she worked at the Norwood Branch Library.

She was extremely polite and friendly, and I guess I never expected her to say anything other than what she did. If I worked for a library system that had switched to computer catalogs, I wouldn’t publicly long for old card catalogs. And I wouldn’t badmouth computers either.

She answered my every question politely but firmly and gave good reasons for refuting my objections. The computer catalog saves time, she told me, and offers so much more to the user. She insisted on showing and proving this to me and asked me to give her and author or a book to find.

I gave her Ferrol Sam’s, a rather obscure Southern writer. She pressed some keys and showed me that he had written five books and told me which libraries had certain copies. I couldn’t see why this would save me any time, but she insisted that it would.

But what about readers? Did they accept it and were there problems, I asked. There was dismay, at first, she told me, but people generally have accepted it.

In the New Yorker article, Baker told how the University of Maryland held a ceremony at the dumping of their old card catalog. They tied cards from the file to hundreds of balloons and released them to fly across the country.

Ms. Wilson smiled at this story. She believed the cards in Hamilton County were recycled, she said. She was certain no balloons were involved, and that no ceremony was held.

You might think that older people would have more objections to the computer file, while young readers would take to it. Not true, said Baker in his article.

In a study, 65 percent of tested fourth-, sixth- and eighth-graders were successful in card catalog searches, while only 18 percent were successful in computer searches. No fourth-graders used the computer card catalog successfully.

So, to test the youth theory here, I approached a well-dressed, young woman, probably in her 20’s with an armload of books and two youngsters in tow.

When I asked her if she used the library often, she told me that she used it all the time. When I asked her how she liked the computer card catalog, she said, “I’ve never used it.” Then she glanced at the row of computers as if they were a row of black widow spiders. “No. Oh, no,” she said. “I wouldn’t use it.” And she hurried off.

So much for the youth acceptance theory.

Baker’s argument for the card catalog in his article seemed to be primarily a sentimental one. And of course, that is my reason too.

Still, he gave practical arguments against the computer system. Online Computer Library Center owns the largest database of book information in the world, he says, and they contract with libraries to transfer old catalog cards to machine-readable form. They hire operators to do this, who, in some cases, have no more than high school educations.

He compares this to highly trained librarians who have devoted their lives to the knowledge and the loving keeping of books, who over the years wrote and compiled the card catalogs. He refers to their catalogs as “manuscripts” and regrets the loss of their history, and speaks lovingly of the aura they projected.

My sentiments exactly. I do not give up on history easily, and I’m sentimental about things that have stood the test of time.

But Ms. Wilson has convinced me that I should give the new computer catalog a chance. Maybe I’ll actually grow fond of it. At least, I’ll try not to be intimidated by it.

Let’s see… First, you press “1.” And then you press “Enter.” Simple enough so far. Maybe even I could get the hang of it.

But it still bugs me to think that my card catalog was recycled, without even asking my permission.